Offerings in boundary areas gave protection

Different types of boundary and transitions – under floor, thresholds and post-holes in buildings, ditches and burial mounds – were significant. The same is true of geographical features, such as hills, steep cliff faces, bare rocks, glacial erratics, marshes and seashores. These places are viewed as zones where two or more concepts and approaches to existence could meet.

They became natural sites for offerings, where objects thought to be full of power were placed. Many hoards with silver objects have been found in such boundary areas.

The aim of placing such offerings was to ensure oneself of protection and prosperity. But they were not static. Objects could be placed and removed, perhaps for new rituals, or because they were needed for trade.

A leather pouch full of silver

In Sundveda, between Sigtuna and Märsta in the county of Uppland, there is a kind of burial monument that was already old in the Viking times. Objects have been deposited there on two different occasions.

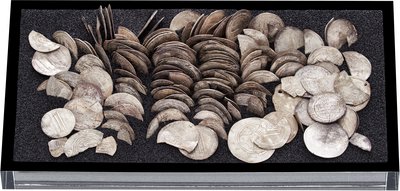

Around the turn of the 8th century the burnt remnants of a person were buried in a ceramic vessel which was placed by a boulder in the middle of the monument. 150-200 years later, in the middle or latter parts of the 9th century, a bag or leather pouch with about 500 silver coins was deposited. Most of the coins were split, which is common for hoards.

The dates of the coins span several hundred years. All except one come from the Persian Empire or caliphate. Many of them are unusual, and include Persian drachma minted as far back as the period 459–484. The only West European find was a fragmented Carolingian coin, minted during the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious, 813–840.

Several thousand years of offerings

In 1913, a number of silver coins and other silver objects such as jewellery, neck and arm rings were found near the Sandtorp farmstead, in the parish of Viby in Närke. The hoard was found when a former bog was ploughed up. Deposits and offerings have probably been placed in the bog for thousands of years.

There are few details of how the hoard was found, but the objects seem to have lain within a limited area. This suggests that the hoard was gathered in a container or a sack. Most of the almost 900 coins were German or English. The youngest coin was minted in 1035, which reveals that the hoard must have been deposited after that decade at the earliest.

One part of the discovered hoard was given to Uppsala University Museum, a.k.a. Gustavianum, one part to the Swedish History Museum, while other finds in the hoard are thought never to have been handed in, including 200 of the coins.

A treasure chest under the floor

In 2009 in the village of Skedstad, in the parish of Bredsätra on the island of Öland, the largest hoard of silver ever found on the island was discovered. It was found in ploughed agricultural land and consisted of almost 1,200 coins which had lain in a container or small chest of wood and birch bark. The hoard was probably deposited in the same way as many others on Gotland and Öland, under the floor in a building which has long since disappeared.

One of the coins is from the time when Olaf Haraldsson (Saint Olaf, Olaf the Holy) was King of Norway, 1015–1028. Olaf died in 1030, and the hoard was probably deposited at that time.

The other coins are older. Most of them are Islamic, but some are from Byzantium, the Carolingian Empire and England. An Indian coin is a unique find for Scandinavia.

Earlier finds in the same field along with archaeological investigations in the surrounding area show that there was a farm here. It has a long history with roots in the early Scandinavian Iron Age, i.e. 300 – 400 years before the beginning of the Viking Age. In the remains of an excavated house, in a post-hole, a hoard of gold from about 400–550 was found, 7 whole and 26 parts of broken rings.